Posted by: The Sumaira Foundation in MOG, ON, Proche-aidant.e, Voices of NMO

The strange phenomenon went away in a few minutes. Her mother, Kimberlie, attributed the problem to Virginia’s allergies. But when the vision problem returned, they went to an eye doctor. The physician diagnosed inflammation of the optic nerve and sent Virginia to the hospital.

The strange phenomenon went away in a few minutes. Her mother, Kimberlie, attributed the problem to Virginia’s allergies. But when the vision problem returned, they went to an eye doctor. The physician diagnosed inflammation of the optic nerve and sent Virginia to the hospital.

While waiting and waiting for admittance to West Virginia University Hospital for an MRI, her parents could wait no longer, so they took Virginia to the ER. From there, she was admitted to wait for the imaging. They were told it would probably be the middle of the night before her MRI because she was not high priority. While waiting, Virginia fainted, which moved her up on the priority list. They diagnosed her with optic neuritis. She was then treated with IV steroids. She was given a spinal tap and had all her blood work done. The doctors thought she had MS. After five days in the hospital, they sent Virginia home with an oral steroid taper.

Virginia’s legs felt a “little odd”. The professionals thought it was stress or anxiety. She knew they thought she was making it up. About three weeks later, both of Virginia’s legs were insensate to touch. Her vision had not returned. Then, her knees locked in place – she could not bend them at all, her toes curled up and her feet twisted to the side. She could only walk with a cane she fondly named “Rosie”.

Kimberlie took Virginia back to the hospital where she was again admitted, and given another MRI, this time of her eyes, brain and spine. Again, the doctors questioned Virginia’s description of her leg symptoms. They provided no treatment. All they suggested was physical therapy. Kimberlie let loose with fury at the doctors who questioned her daughter’s veracity.

As a mother of a child who had sudden, terrifying and unexplained symptoms, Kimberlie had done her homework. Google had become her friend. So that day in the hospital, when nobody believed her daughter, Kimberlie pulled out the lab report and noted that Virginia was positive for the MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) antibody. She showed it to the doctor and demanded, “Isn’t this what this is?” The doctor replied, “Maybe, we don’t know much about this. Come back in three months and we’ll take another MRI.” So Kimberlie made an appointment with the doctor whose name kept appearing in many of her Google searches.

Over the summer, Virginia’s legs stopped working entirely for periods of time, during which she had to scoot along the floor to move. She was still half blind. Her parents took videos of everything they saw in their daughter. And then, in early August, Virginia, her mom, and her dad flew north to see Dr. Michael Levy at Massachusetts General Hospital. Her two younger sisters stayed behind with family.

Dr. Levy saw Virginia’s blood work and the videos, and immediately knew that Virginia had MOG antibody disorder. Mom, dad, and daughter, for the first time in months, didn’t feel crazy. He prescribed CellCept, but over the next few months, Virginia lost the ability to walk entirely. She attended school in a wheelchair. Dr. Levy therefore changed the prescription to IVIG. Though there was a national shortage, West Virginia University Children’s Hospital had the therapy.

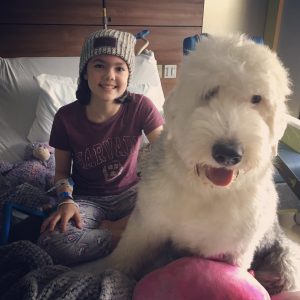

Virginia received her first infusions in October over three days. The infusions gave her severe nausea and headaches. But a few days after she got home, she was able to walk with a walker. Two weeks after that, Virginia could walk with Rosie. And a few months later, she was able to walk on her own.

Each monthly IVIG infusion continues to cause headaches and nausea for a few days. But other than that, Virginia has only a blind spot in the middle of her vision on the left, with a “halo” around the spot. Apart from periodic headaches, loss of vision, and some soreness, she feels good. She continues to walk without aid for the most part, only using Rosie from time to time.

But here’s the story about Virginia. When her symptoms arose under a year ago, nobody around them knew anything about her symptoms, so she decided to create a blog https://sweetvirginiasjourney.blogspot.com so that “if I put information out on the web, maybe I can help other little girls.” She also has a Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/sweetvirginiasjourney for the same reason.

When she went to the hospital for her infusions in November, Virginia forgot to bring pajamas. She asked the nurse for some, who brought her a nightgown because they had run out of PJs. Virginia thought,

Virginia and her family live in a town with a population of 650 in West Virginia. Every year before Christmas, the town holds a festival on Main Street. After her November hospital stay, Virginia and Kimberlie got moving. With their local chamber of commerce and the goodwill of volunteers, they offered photos with the Grinch on that Saturday in town. If you brought a pair of pajamas, the photo would be free. Virginia brought over 200 pairs of PJs to the hospital the next day. She and her mother have already committed to a spring pajama-raiser.

Both mother and daughter say that the worst part of everything they’ve gone through was not being believed. Virginia says that other kids can call her. She’ll tell them, “It’s OKAY. I believe you.” Kimberlie says to tell other children to keep saying how they feel until someone believes them. She says to other parents,

She is also adamant that parents should seek second opinions, especially if they’re not comfortable with a first diagnosis, attitude or treatment,

Kimberlie and Virginia and the rest of their family want to help in any way they can. They feel that this gives them some control over a situation that wrenched control from their lives. When they do a pajama drive, they have something good on which to focus. MOG may have caused a major hurdle in Virginia’s young life, but she turned her own experience into something that will help others. And she’s still only 11.

As told to Gabriela Romanow in January 2020